Objectives-based grading’s rise to prominence over traditional grading has been met with mixed support, as we humans are very resistant to change. However, objective-based grading does a better job than points-based grading in many ways, which should be considered. Objectives-based grading clearly communicates what skills are known and what skills still need to be learned, rather than having to decipher that information from points. JT Sugalski ‘24 affirms that objective based grading shows the learning process better, while also making it clear what to work on, as he says “If you started at beginning and now you’re at proficient, it can show some sort of process; here’s where I need to work, here’s where I’ve done a good job.” Recognizing where you are in the learning process makes it easier to know the next step, whether just figuring out a small part or a fundamental concept. And contrary to points-based grading, you aren’t as dependent on the knowledge you came in with or how quickly you understood the material. Andy Cantrell describes this by saying that objectives-based grading “doesn’t penalize people for being faster or slower to pick up on concepts”, meaning that even if you don’t do well on the first test, the cumulative nature of the grading system allows you to demonstrate your knowledge in later tests. Using this model, “incentives learning,” as Cantrell describes it, pushes students to deeply understand a concept in the long term rather than forgetting it after the test. A common gripe with the system is that it makes grading convoluted, as Sugalski echoes by saying “it’s kind of difficult to understand and everyone is different, if it was standardized I feel like it could be better.” Because objectives-based grading is relatively new, there are bound to be some imperfections, but they will be smoothed out over time. Cantrell says “There are problems which have to be worked out, and the end result is much better” in reference to the process of teachers figuring out the best way to apply objective based grading to their courses. Over time, as we and the school adapt to this system, it will end up being ideal compared to a points based grading system.

Objective-based grading is an assessment strategy that focuses on defining learning objectives or outcomes. So basically instead of assigning a single overall grade, students are evaluated based on their proficiency in specific objectives. However, these objectives are goals that describe the knowledge or skills students are expected to accomplish.

Teachers create a set of scales relating to each objective. Students are then assessed against these scales, providing a more detailed and clear view of their performance. This approach helps educators to offer engaging feedback relating to their accomplishments and mistakes, helping students understand their strengths and areas needing improvement.

Objective-based grading makes it easier to track and assess progress. Students and parents appreciate the clarity and specificity in feedback, engaging in a deeper understanding of learning expectations. It encourages a growth mindset by emphasizing skill development and mastery of the content given in a classroom.

Objectives-based Grading can oversimplify learning by reducing skills and knowledge to discrete objectives. Critics argue it may neglect the understanding of a subject. The exact focus on objectives might also decrease creativity and critical thinking. Additionally, objectives- based grading may not capture the full spectrum of a student’s abilities, limiting the educational experience and the importance of the assessment.

With change brings controversy, and subsequently division. The enactment of objective-based grading in several classes has invoked such. Among the student body, the consensus is clear: no to objective-based grading. Students alike can agree that, in select classes, the seemingly newly developed system of objective-based grading has been confusing and lacking in transparency. Conversely, standards-based grading is intensely seeped in transparency, almost to an extreme. To the student’s eye, objective-based grading creates confusion rather than curbing it. According to Carson Rosenbaum ‘25, objective-based grading inhibits students’ representation of their knowledge in the class, “I think objective-based grading is not helpful to student’s learning because it’s an imprecise metric of how well they’re doing… the difference between a Developing and Proficient is so wide… so it’s harder to gauge how you’re doing.” In agreement with Rosenbaum, Christian Hovard ‘25 provides an anecdote from AP US History the previous year, “last year I got… what is equivalent to a developing or even a beginning on a test, but I was still able to climb back up… [at] the end of the year… and that would not have been possible if [it was] objective based grading because I would have been locked in with that developing or that beginning… that would [not] have been reflective.” Hovard further expresses his frustration with understanding how the grading system works, “I have a harder time understanding how my grade is calculated than what I’m doing with my grade than the actual material in the class.”

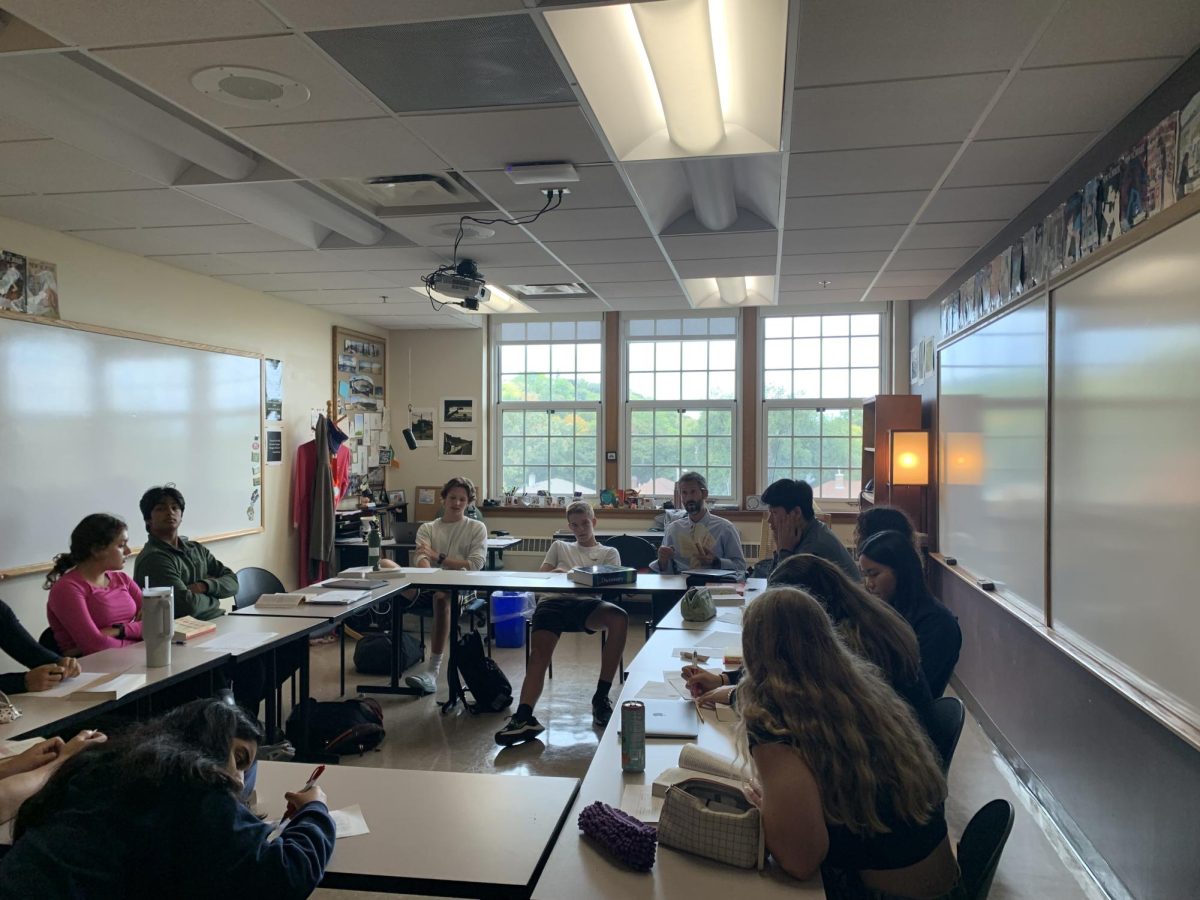

Physics teacher Maggie Molter has used objective-based grading “for nearly 10 years,” and has expressed concern for the growing narrative surrounding the changes the upper school is experiencing in the newfound grading system, “I think that this can easily become something like teachers versus students–and it already has.” Molter reasons that the growing distance is fueled by confusion and newness, “adjusting to anything new there can be some feeling of anxiety or discomfort and that’s the main challenge is just to hold space for students to ask questions and make sure folks understand how it works.” While change is vital to progressing methods of learning, the development of increasing student-teacher transparency and that are causing students. Molter acts as a success story in this system, which she attributes to the relationship between a teacher and a student, “you can make a big change without having a relationship, so I… the system that I’m using in physics has developed over 10 years of conversations with students who are experiencing the grading system from a different perspective.” Currently, classes do not fit these standards. While the objective-based grading system may prove to be beneficial in a sum of years, teachers who have not used this grading system previously appear to be far too ambitious and lead to inflammation in the student body surrounding the topic. Molter’s carefully crafted strategies towards the system have proven successful, the general student body does not express comfortability in differing classes. It appears that with time comes improvement, but is the student body willing to take up to 10 years to find success?